Beginning Farmers – Why I Bother: Philip Reid

My father, Philip Reid died in his bed at his home in Williamsburg, Massachusetts at 3:22 am on Sunday March 4th 2012. His wife (my stepmother), my sister, and my own wife were all with him as he took his last breath. Of course I am very sad, but he was ready to go, at peace with the world, and had realized several months before that this was a fight he couldn’t win, and no longer had the strength to engage in.

My reason for writing this is not to elicit sympathy. But rather, to explain a little bit about my father’s role in helping to cultivate my passion for farming, and my reason for starting and nurturing this project – by which I mean Beginning Farmers. This is why I bother.

I was not born on a farm, but from the age of two I lived next door to one. And it was mostly because of my father that the farm was an extremely important part of my life growing up. I have written a little bit about this before – in a post about the Clark Farm in Williamsburg, MA.

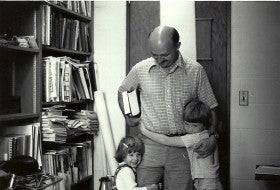

My father took a job as a botany professor at Smith College in Northampton, MA in 1971, when I was a year old. But soon, he and my mother moved to a rural community where they could have a garden and where he was closer to his roots. Growing up in Michigan, his parents had always has a big garden. His love of plants was not just an academic pursuit. He loved tending to them, nurturing them, and observing them, as well as studying why they did the mysterious and magical things they did.

His Masters Degree thesis was a study of sunflowers on Tucker Prairie in Missouri, one of the last native pieces of prairie land in America which has never been plowed or sown. He studied the allelopathic (tendency to exude chemicals which inhibit the growth of other plants) nature of sunflowers.

While never religious, my father was “spiritual” in certain ways, and asked himself questions about the world that are similar to many of the questions I have asked myself about it. From a personal writing of his in 2008: “As I sit on my deck and look at my woods, I wonder – are these woods really mine?… What I see looking to North looks like orchestrated movements, rather than the “twittering of aspen”. The forest movements are bigger. They are like waves in the ocean… beautiful… exciting”.

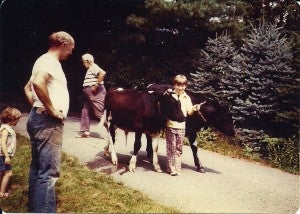

My father took an interest in the farm next door to our house right away. And we spent many hours there, helping to put hay in the barn, helping to feed the cows, and helping to deliver them, when it was needed. One of my earliest memories is knocking bales down from the top of the wagon for my dad to load on the conveyer. It’s a shame I have no pictures of that, but it’s not surprising. It was about community, comradeship, and getting things done. Not a time for cataloging memories.

Linwood would be at the top of the conveyer, tossing the bales my father loaded into the loft. And my father always said he had the easy job. But I remember my dad sweating so hard I didn’t think anyone could contain that much water, and waking up the next day so covered in poison ivy blisters that he could barely move. But he was always there. And I was there with him, whenever I could be.

He was dedicated to his work as a scientist. But he was also dedicated to his work as a father, and as a community member. The latter of which included making maple syrup with the Clark’s the old fashioned way – tapping the trees with a hand drill, pounding taps into the holes, attaching buckets under the taps. Then spending hours every day, when

the sap was running well, hauling it to the the syrup house – which was an old caboose from a parade they’d once held in town.

I’d spend nights on end there (it was the only time I was allowed to stay up late), helping to feed the fire, listening to stories and dirty jokes and being shown the stars and constellations outside. I learned some of their names, but as it turned out, I was more interested in learning to swear, to spit, and to understand what it was to be a small dairy farmer in rural Massachusetts in the 1970’s and ’80’s. And it wasn’t easy, even for folks who owned their land and had help from their sons and neighbors.

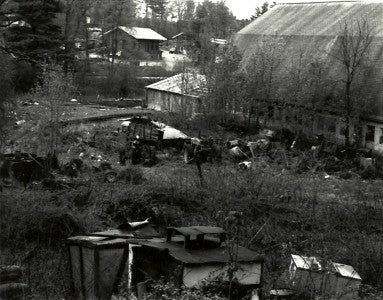

The old farm is a lumberyard now, which is the primary reason my father and his wife moved away. The community dissolved with the loss of the farm. And that’s a big part of why I do what I do here. And why I have been doing it for so long.

I will miss my father so much. My life will be different without him. But he instilled values in me which I will continue to hold and adhere to. This site is his work as much as it is mine, and I will thank him every day, as everyone who has ever used the site should, for the love of small farms, the appreciation of their value, and the sense of moral obligation he gave me to do the right thing.

Beginning Farmers is the equivalent of throwing hay on they belt. I don’t get paid, but there is a sense of community, a sense of work well done, and a sense that what I do every day is important. And unlike my dad throwing bales, I don’t wake up the next day covered with poison ivy blisters.

I will miss you Philip Reid, and I thank you for all you have given me.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices

Nice Blog !

I Like This Very Much.

That was a lovely piece and the photos are very moving. My condolences to you and yours. Let me just: you are a lucky man to have grown up in such an environment. Thanks for the work you do.

Thanks a lot Andy. I really appreciate it.

Taylor

That was a lovely piece and the photos are very moving. My condolences to you and yours. Let me just say: you are a lucky man to have grown up in such an environment. Thanks for the work you do.

I lived across the street from your dad for 9 years in Williamsburg. He was a very special person. I would bring the children from my daycare over to visit and he would give them a tour of his gardens and if anything was ready to be harvested he would share samples with the children. What a lovely man. I miss him. Take care.

Thanks Erin. Was nice to meet you last week. Take care.

Taylor

I am so sorry for your loss. This is a beautiful and inspiring tribute to your father. Thank you for sharing, and for continuing to do what you do.

Thanks Robin. Appreciate your thoughts.

Taylor

A very nice tribute to your father. Our thoughts are with you Taylor.

I really appreciate you reading the post. Thanks for your thoughts – that means a lot to me.

taylor

We connected to your Dad through the UMASS-Botany Department. My husband Peter was a graduate student in Bernie Rubinstein’s lab in the early “70s and that is how we met Phil. We also saw him guide NEASPB up through the 1990s; he was really the lifeblood of the organization. Phil was a genuinely nice man. He loved what he did and what a lovely legacy he left for us all. I too genuinely love to be in the garden. Your Dad will be remembered among those who have given much to make life beautiful and bountiful.

Thanks Janice. My dad respected Peter a lot. And I respect him EVEN MORE knowing he was Bernie’s student. I had a class with Bernie when I was an undergraduate and I’m pretty sure I never worked so hard for a “B”. Perhaps that’s just evidence that an aptitude for plant physiology is not a genetic trait that’s inherited paternally. Anyway, thanks for the kind words. I really appreciate hearing this stuff.

Take care, Taylor

Very moving, T.

kjw